It’s not easy to articulate what kind of mark a fiftieth anniversary represents. Those who remain married for fifty years call it their Golden anniversary (or Golden Jubilee) and, while it’s no uncommon to live longer in the twenty-first century, fifty years is still a pretty significant event – it is half a century, after all. The point, ultimately is that a lot of life happens in fifty years and, when the occasion arrises, it’s only right to recognize and celebrate it.

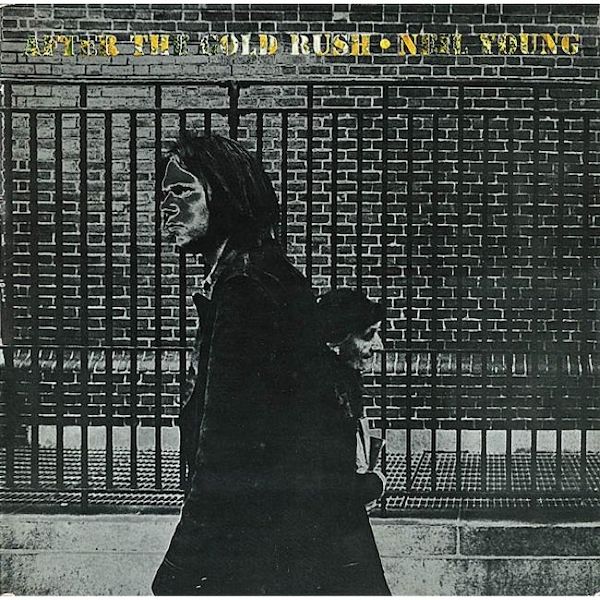

While it might not have seemed like it at the time, After The Gold Rush was a significant event in Neil Young’s artistic development. Sure – it might not have seemed that way at the time; After The Gold Rush was Young’s third solo album (not his first, not even his first significant breakthrough, really), and it wasn’t released at a particularly notable moment in history (all the spectacular things which had happened in the Sixties felt like they were already well-into the rearview mirror) and it wasn’t terribly well-received at the time (Langdon Winner commented that, “None of the songs here rise above the uniformly dull surface” in Rolling Stone upon the album’s release, and Robert Christgau was only slightly more charitable in the Village Voice). Even so, somehow the album endured and even began to age into a sepia-toned nostalgia which was easy enough to appreciate, with some distance – particularly when the singer began pushing boundaries and drawing creative lines in the sand that not every fan was comfortable with following (like the crudity inherent to On The Beach in 1974, the great big rock posturing of Tonight’s The Night in 1975, and pretty much every creative turn Neil Young made from 1979 to 1996 – which is characterized by fans either loving or hating each new development, on an album-to-album basis). As the singer’s catalogue further unfolded and became marked by albums both great and poor, listeners found themselves looking more fondly on After The Gold Rush because it wasn’t shocking or difficult or more experimental than they could take – it was just an exposition of a great songwriter’s talent which didn’t seek to be challenging too.

Listening back to it now – with the benefit of hindsight – delving into After The Gold Rush is an even richer experience. As “Tell Me Why” opens the A-side, listeners will easily be able to feel the warmth and affection for the Sixties (and Neil Young’s work with Crosby, Stills and Nash during that decade) all around it as the breathless vocal harmonies in the song intertwine with Young’s guitar and leave them feeling as though not all was lost at the collapse of the previous decade; peace, love and hippies hadn’t defeated Nixon, but darkness hadn’t yet consumed the world either. There’s a certain beauty about the song which is capable of winning hearts and making eyes glisten, to this day.

After “Tell Me Why” opens the running for After The Gold Rush though, the energy in the A-side’s play begins to change dramatically. The album’s title track follows “Tell Me Why” and finds Neil Young putting his guitar down to let a simply and gently-played piano take the focus. The results are startlingly captivating to this day; Young begins to broach many of the conversations the singer has debated perennially ever since (and, in this day and age, it feels so cool to hear the singer deliver lines like, “There was a fanfare blowing to the sun that was floating on the breeze/ Look at Mother Nature on the run in the 1970s” and recognize that some of the same thoughts and ideas are still relevant a half-century later, in the era after Donald Trump’s presidency), and manages to tie them to images of lying in burnt out basements and discovering revelations in desperation feel heartwarming and tranquil – in spite of the fact that all of them are pretty far from that. That kind of desperation and sadness gets tied to the “Sixties last gasp” vibe which appeared in “Tell Me Why” for the sort of post-script to the era of peace and love exemplified by “Only Love Can Break Your Heart,” before “Southern Man” re-evaluates the state of faith against oppression and vice in a very dry-eyed and didactic manner, and then “Till The Morning Comes” spontaneously pulls up and points the direction of After The Gold Rush upward (with horns and a more jovial rhythm) to close the side. Compared with the darker thematic turns that the A-side of After The Gold Rush took earlier, “Till The Morning Comes” ends up feeling like it doesn’t fit in at all; the piano which opens the cut feels like it could have been lifted out of a tenpenny orchestra, the lyrics feel phoned in and the brevity of the song makes it feel like filler. Of course, it isn’t filler – the whole point of “Till The Morning Comes” [editor’s note: the spelling in this song title drives me crazy – “’Til’ is how one abbreviates “Until,” “Till” is the thing a cashier counts at the end of their shift, but this review utilizes the spelling on the back cover of the album, so here we are –ed] is to bridge the A-side of After The Gold Rush with the B-, but actively listening to the song (as one does, when one is reviewing it) inspires more questions than it answers.

As the B-side opens, “Oh Lonesome Me” again plays a bit like a throwback to the decade which came prior to After The Gold Rush original release (lyrics like, “Everybody is going out and having fun/ I’m a fool for staying home and having none”) and plays a lot like the hangover to the big party from the night before – particularly with the song’s loose arrangement in hand before sobering up nicely for “Don’t Let It Bring You Down” – which follows it. There, Neil Young presents listeners with a song that would someday come to be regarded as a classic for all the tones it exhibits: the “old man”in the song is the personification of the dying trends and shifting values now as faded as the denim pants photographed on the back cover of the album set to an undeniable and rock-solid rhythm which is capable of getting stuck for days in the minds of those who hear it, the “blind man”is the personification of those who (to paraphrase Plato)have yet to be enlightened and the poetic articulation of a crime scene is a perfect illustration of where the world was in 1970 – and how it still needed to proceed forward (some would say, “how it still needs to proceed forward”).

That faded denim image, covered with patches, on the back cover of After The Gild Rush gets a little more exercise with the Sixties Rock tones which bleed through “When You Dance (I Can Really Love)”. There, Crazy Horse doesn’t really attempt to establish themselves as the unique counterpoint they’d become for Neil Young before the end of the Seventies, and endeavors to just fill in the mix ably, and remains in the proverbial wings for “I Believe In You” before helping Young crib the rhythm and tone that The Band had built up perfectly for “The Weight” just a couple of years earlier for “Cripple Creek Ferry,” which closes the album gracefully.

Now fifty years later, while After The Gold Rush did not originally come out with great fanfare, the album has aged surprisingly well. Putting the album on now does not leave a single cringeworthy turn anywhere in its running at all; other than the mention of the decade which preceded the album’s release in the title track, an easy case could be made for After The Gold Rush being timeless; the songs are lush, low key and beautiful, as are the melodies, and nothing stands out as being anachronistic. That is not at all something that other albums of the same vintage can claim; being able to stand up as well as After The Gold Rush does fifty years after its original release is a genuine rarity which deserves to be recognized.

Leave a Reply