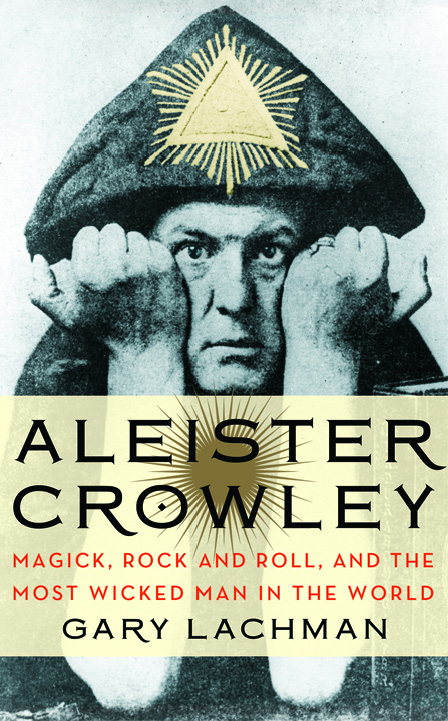

Aleister Crowley: Magick, Rock and Roll, and the Most Wicked Man in the World

Written by Gary Lachman

Published by Tarcher/Penguin

There can be few music fans that aren’t aware of the name Aleister Crowley. From The Beatles through to Black Sabbath and Iron Maiden, Crowley (AKA The Beast 666) enjoys a bountiful afterlife.

Much has been written about Aleister Crowley, and in my experience, it veers between the extremes of either condemning or eulogizing him. Gary Lachman’s book is a much-needed panacea to such works. Gary is a rare writer. He knows and understands what he writes about but has a disciplined and fair approach to his subject. You could say he wears neither rose-tinted spectacles nor dark glasses: his approach sees Crowley’s work, life, and the effects of both as clearly as possible.

Gary was a musician himself. He was part of the 1970s New York scene and was a member of the band Blondie, and later even played with another icon of extreme behaviour, Iggy Pop. When you add this to his extensive knowledge of magic, the occult, and those involved in it, you have the ideal author to approach Crowley in a new light for the 21st century.

So, why are people still interested in Aleister Crowley, his works, and his life, so many years after his death in 1947 — a death in relative obscurity? (See Netherwood: The Last Resort of Aleister Crowley, London, Accumulator Press, 2012, for more on the last days of The Beast). It was Crowley’s appearance on the cover of The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s album that really brought Crowley back into the public’s consciousness. Since then he has enjoyed a high posthumous profile.

Gary’s book is more than just a biography of The Beast (though he makes an admirable study of Crowley’s life and posthumous afterlife). He also brings his own experience to bear on Crowley’s behaviour and magick (the two are very much linked to each other) and comes to his own startling and fascinating conclusions. Gary does not see Crowley as ‘the wickedest man in the world’ (as the tabloid press of Crowley’s day dubbed him), nor does he see him as some kind of perfect occult hero. Rather, Gary sees Crowley as a brave though badly flawed explorer and experimenter, a man who wanted to experience as much as possible but was hampered by the burden of a colossal self-serving ego, and blind to the consequences of his own action to both himself and others. It’s a very accessible book but one that shows a profound understanding of not just its subject but of life itself.

Lachman writes of reading Crowley’s The Diary of a Drug Fiend in a day or two: ‘I was especially struck by the quotation from the seventh-century philosopher Joseph Glanvil that opens the book: “Man is not subjected to the angels, not even unto death utterly, save through the weakness of his own feeble will.” It’s easy to see how this inspired Crowley’s often quoted and usually misunderstood maxim: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.” “Love is the law, love under will.”‘ To my mind far more significant was Crowley’s definition of magic (or ‘magick’ as he later styled it) as “the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity to will.” Will or thelema is a major part of any study of Crowley.

Gary deals well with the description of Crowley as ‘The Wickedest Man In The World,’ writing: ‘That Crowley was an egotist and mistreated the people in his life—was, indeed, wicked—are not the most important aspects to his career. Other less interesting characters have done the same without having Crowley’s flashes of genius, although, to be sure, Crowley’s ignominy was considerable. Yet for all his inexcusable behaviour, Crowley was not “evil” in the sense that, say, Sherlock Holmes’ adversary, Professor Moriarty, was, or the black magicians of the many occult horror films that Crowley inspired were. Crowley was not evil, only insensitive, selfish, and driven by a hunger he seemed unable to satisfy and an incorrigible need to be distracted. . . . Crowley was not evil, but his need for excess, for “strong” things, more times than not was a source of suffering for those around him.’

But ironically, none of these “strong” things truly made Crowley happy, as Gary writes: ‘Crowley found that his “happiest moments were when he was alone in the mountains” and that his happiness in no way derived from mysticism. “The beauty of form and colour, the physical exhilaration of exercise, and the mental stimulation of finding one’s way in difficult country formed the sole elements of my rapture.” At this point Crowley achieves an insight into his psychology that one can only regret did not register more firmly.’

Lachman also suggests that Crowley was motivated less by his “real self” and more by a sense of his “self-image”: ‘Crowley’s persona of the Beast 666 was a response to other people. It was a problem he was saddled with throughout his life. . . . It was Crowley’s awareness of other people—“the pressure”—that drove him to “Satanize,” that is, to shock and scandalise. . . . Crowley escaped from his self when he was mountains, but when he came down to the low-lands, the “pressure” returned and he fell back into the habit of “satanizing.”’

While he’s never cynical about some of Crowley’s more outlandish claims, Lachman does have a good sense of humour about them (another thing I love about the book!). He tells us: ‘One night, returning from dinner with George Cecil Jones, Crowley found a rather large and mysterious magical cat on his stairwell. His white temple had been broken into, the altar was overturned, and the furnishings scattered about. Crowley says that 316 demons ran about the place, which suggests either very small demons or a very large flat.’

The same sense of humour is applied to Crowley’s purchase of one of his now infamous homes: ‘Boleskine was a long, low building on the southeast rise overlooking Loch Ness, halfway between Inverfarigaig and Foyers in Scotland; years later, Jimmy Page bought the place, and today it remains a site of thelemic pilgrimage. At the time Crowley moved in, the Loch Ness Monster was yet to appear—the first sighting was in 1933—and one of the oddest explanations for Nessie’s existence (if she does exist) is that Crowley was somehow responsible. (I’m not sure if Crowley actually took credit for this, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he did.)’

I might add in a further humorous vein that in another book I read on Crowley, The Beast convinced a guest that the environs of Boleskine were inhabited by wild haggis! (For those who don’t know, a haggis is a unique Scottish dish, not an indigenous Scottish species.)

Lachman gives fair credence to Crowley’s claims of the origins of his most influential work, writing: ‘Although the most likely origin of The Book of the Law is Crowley’s own unconscious mind, I accept the possibility that it may have come from a disembodied intelligence of some kind. I don’t rule out the possibility of such intelligences, although, I must admit, I have had no experience of them… Two of Crowley’s contemporaries, however, did. W.B. Yeats and C. G Jung both produced work that they claimed originated in a similar mysterious source. Yeats’ ‘A Vision’ (1925), which presents a unique system of personality types based on the phases of the moon (and which deserves more notice) was “transmitted” by his wife through automatic writing; strangely, this happened on their honey-moon, just as with Rose and Crowley. And Jung’s strange Gnostic document ‘The Seven Sermons to the Dead’ (Ca. 1916) came to him in a kind of waking dream, communicated by voices who had “come back from Jerusalem” where they “found not what we sought.” Both ‘The Seven Sermons to the Dead’ and ‘The Book of the Law’ are written in a bombastic, quasi-biblical style, which Jung said was the language of the archetypes. That both Jung and Crowley knew their Bible must have had something to do with them; Jung’s family, too, was deeply religious. And Jung too, believed that he communicated with “discarnate” beings such as his “inner guru,” Phileman.’

One of most remarkable things in Gary’s book is that Crowley had an amazing insight, but one that he sadly failed to apply to himself, we’re told: ‘”The key to genius is quieting the mind. … It is by freeing the mind of external influences… that it obtains the power to see the truth of things.” For all his being the ‘spirit of solitude,’ Crowley spent very little time alone- some of his “magical retirements” were taken at the best hotel in town. He was practically always surrounded buy people, an example of his following the small part of himself rather than the great.’

I recently read P.D James’ book Talking About Detective Fiction, and she very ably makes the point that the source of creativity is mysterious; Gary feels that source of Crowley’s magick was much the same, finding his ‘most important remarks … about magick’ in the Confessions: ‘“Even the crudest magick eludes consciousness altogether,” he writes, “so that when one is able to do it, one does it without conscious comprehension, very much as one makes a good stroke at cricket or billiards. One cannot give an intellectual explanation of the rough working involved.” . . . My belief is that Crowley’s magick, when it worked, somehow induced synchronicities. But Crowley did not know how he did this. He admits that most magicians suffer from the delusion that there is a “real apodeictic correlation between the various elements of the operation” and its results, meaning they believe the circle, sigils, weapons, et cetera are necessary for the operation to work (apodeictic means “necessarily true” and is a term used in logic). Crowley knew they were not, yet he continued to use them. But he also knew that success in magick “depends on one’s ability to awaken the creative genius which is the inalienable heirloom in every son of man.” The “creative genius” was one of Crowley’s phrases for the unconscious. So successful magick depends on throwing oneself into the unconscious, something Crowley was familiar with and pursued throughout his career.’

In many respects, Lachman found a very immature aspect to Crowley’s character: ‘”Man has the right to live by his own laws,” Crowley declares. He has the right to work, play, rest, die, and love as he will and he has the right “to kill those who would thwart these rights.” The essence of these “rights of man” is the same as Crowley’s earliest desire to “let me go my own way,” the adolescent need to “do what I want to do” without interference. Like the oft-quoted line from his poem, ‘”Hymn to Lucifer”—“The Key of Joy is Disobedience”—Crowley’s “rights of man” remind us that Crowley never grew up. This is one of the truly remarkable things about him. Crowley swallowed enough experience to fill a dozen lives yet he emerges from it all exactly as he began. He remains a colossal example of arrested development.’

Finally, Lachman has found that we have become inured to much of what Crowley stood for (his era of “force and fire,” his “excess in all directions”’). He both asks and answers a very important question, not just about Aleister Crowley, but about us and the world we now live in: ‘Does this mean that Crowley was right and the new age he prophesised has arrived? Not really. What it means, I think, is that Crowley was a kind of pre-echo of our own moral and spiritual vacuum. For better or worse, we do find ourselves in an antinomian world, beyond good and evil, in which practically anything goes and we are urged to give into our impulses and “just do it.” If nothing else, giving in to impulse is good for business. But we live in a world with constant distractions, constant allurement to have, do, or be “more”—we have so lost touch with life that we have to “capture” it on our cellphones, as if it were a wild creature on the loose, and display our trophies on social networks. We are very far from Pascal’s suggestion that we sit quietly in a room… But if Crowley was right, and this is the era of the “crowned and conquering child,” I can only hope that he grows up soon.’

This is a good point. (Recently at a concert I was struck by now many people were busy filming the concert on their phones, rather than living the moment and enjoying the music.) And this is a fine book by a fine author, one with great knowledge, wit, and insight, and one the reader will enjoy going back to again and again.

Leave a Reply